How Johannes Brahms’ German Requiem reinvented the genre as a celebration of life

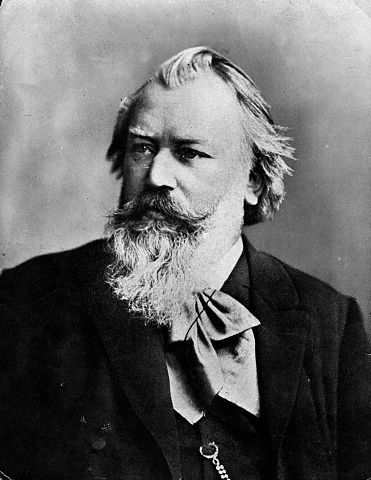

Grief manifests in mysterious ways, affecting us in painful, heart wrenching ways that leave a lasting emotional and physical toll like a scar etched forever onto your soul. It can also be the impetus for creation, as was the case for Johannes Brahms, whose grief fueled a composition so profound that it has endured as one of the most revered symphonic works of all time.

Johannes Brahms had just received an urgent telegram from his brother Fritz: “If you want to see our mother once again, come immediately.” At age 76 their mother, Christiane Brahms, had had a stroke. Brahms rushed to reach her, but she had already passed away by the time he arrived. The loss affected the composer profoundly, and almost immediately he began work on A German Requiem.

Though the death of his mother was the immediate catalyst for the work, it is possible that the idea for it originated after the death of his mentor Robert Schumann nine years earlier. It was Schumann who had first made the young, unknown Brahms famous by declaring him Beethoven’s heir in a widely read music publication. In the years since, however, Brahms had struggled to convince the musical world that he was worthy of Schumann’s prophecy. A German Requiem would at last convince many that Schumann was right. Upon completion, it became the central work of Brahms’ career, the one that established him as a composer of major stature and linked two of the most important spheres of his lifelong musical endeavor, the vocal and the symphonic.

Brahms gave no indication of whose memorial the Requiem might be, if indeed it was any one person’s. As with all great music, the universal message of its vision transcends the circumstances of its conception. His remark that “I would very gladly omit the ‘German’ as well, and simply put ‘of Mankind,’” suggests that he wished to offer this solace to all listeners, regardless of their own religious beliefs or backgrounds. “A German Requiem,” it appears, has become something of an anthem for our time, with grand social and political reverberations.

A German Requiem differentiates itself greatly from the requiem masses written by Mozart, Verdi, and Britten, among others, in a number of ways. The work’s title reflects Brahms’ use of the Lutheran Bible rather than the customary Latin one, bypassing the standard liturgical requiem text, with its fearsome Dies Irae, so vividly set by other composers. He compiled the text himself from both Old and New Testaments, and from the Apocrypha. It has little in common with the conventional Requiem Mass, and omits the horrors of the Last Judgement – a central feature of the Catholic liturgy – and any final plea for mercy or prayers for the dead.

Not surprisingly, the title of “Requiem” has at times been called into question, but Brahms’ stated intention was to write a Requiem to comfort the living, not one for the souls of the dead. Rather than dwelling on the judgment of the deceased, he seemed intent on consoling those left behind. For example, he wrote those who “mourn” will be “comforted”; “tears” will reap “joy”; those who “weepeth” will experience “rejoicing.”

It was Brahms who originated the term “human requiem,” in a letter to Clara Schumann, Robert’s widow. This human focus, as well as the work’s freedom from angry religious judgment, makes it easy to seize on in our more vaguely spiritual time.

Whatever the inspiration or the meaning behind the work, the music itself is without question some of the most beautiful and epic ever put to paper. Brahms is often associated with his instrumental works: grand symphonies, dramatic piano concertos, epic chamber works. But A German Requiem represented the culmination of a decade of work for choir. His choral world functions as an idealized democracy, allowing each vocal line to have its own viewpoint, with each independent line working together in perfect harmony.

Featuring sweeping melodies and soaring choral voices, this is an ethereal work of pure beauty that will tug firmly at your heartstrings.

The Colorado Symphony Chorus and two vocal soloists, Karina Gauvin, soprano, and Joshua Hopkins, baritone, lend distinction to this stunning masterpiece alongside the Colorado Symphony and Principal Conductor Peter Oundjian from March 24-26 at Boettcher Concert Hall.