Whatever folks thought they knew about renowned classical and jazz bassist Charles “Charlie” Burrell — his historic place as one of the first Black musicians to sign with a major American orchestra, his collaborations with jazz legends like Billie Holiday and Duke Ellington, his presence as a cornerstone of Denver’s musical life — the truth is, he was even more than that. A titan in both sound and spirit, Burrell embodied a kind of brilliance and generosity that transcended the stage.

On June 17, 2025, Charlie Burrell passed away at the age of 104. He died in Denver, the city he helped shape into a national hub for music and culture, surrounded by a legacy that will long outlive him.

“Our beloved Charles passed away this morning, June 17 at the age of 104,” his family said in a statement. “Born in Toledo, OH on October 4, 1920, Charles was a devoted son, father, husband, brother, uncle, nephew, cousin and friend to many. Charles dedicated his life to his music and inspired the world with his bass. As one of the first African Americans to win an audition with a major symphony orchestra, he opened the doors for musicians of color everywhere. While we are heartbroken at his loss, we are also grateful for his long and inspiring life. Thank you to all who cared about Charles and thank you for all of your prayers.”

“He opened doors for musicians of color everywhere.”

Family of Charles Burrell

Indeed, Charlie Burrell was often called “the Jackie Robinson of classical music.” Though he may not have been the very first Black musician to play with a major American symphony, being the first Black member with the Denver Symphony Orchestra in 1949 enshrined him as a pioneer. But that wasn’t the beginning—or the end—of his trailblazing journey. In 1959, he became the first African American musician to be hired by the San Francisco Symphony. Burrell’s pioneer essence was also felt in education. He was one of the first professors of color at the renowned San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Burrell’s roots in music ran deep. Raised in Depression-era Detroit, he was captivated by the classical music broadcasts of the Detroit Symphony and particularly inspired by a recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony — he resolved, as a young boy, that he would one day play in an orchestra. That dream guided him through racial barriers, financial hardships, and even war.

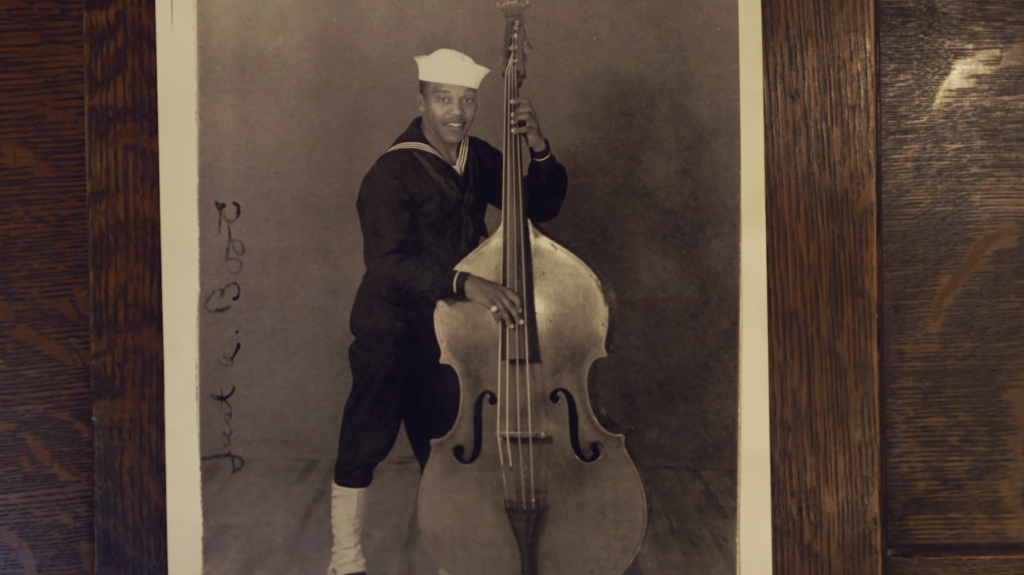

He enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II and was stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Base, where he joined the Navy’s first all-Black band, performing alongside future jazz greats like Clark Terry and Al Grey. Following the war, he studied music at Wayne State University but struggled to find a place in classical music due to the color of his skin. Four orchestras turned him away before fate and a bus ride brought him to Denver.

“He had the heart of a lion and the endurance of an elephant.”

Purnell Steen, jazz pianist

While working as a janitor at Fitzsimons Army Hospital and attending the University of Denver, Burrell struck up a conversation with John VanBuskirk, principal bass of the Denver Symphony. That conversation led to an audition and a historic hire with the Denver Symphony Orchestra (now the Colorado Symphony). Burrell’s orchestral tenure in Denver spanned more than 40 years, from 1949-1959, and upon his return from San Franciso in 1965 until his retirement in 1999.

“Charlie Burrell was a trailblazer for people of color in the orchestra business,” said Basil Vendryes, Colorado Symphony Principal Viola. “He was the first player of color in a major orchestra (the San Francisco Symphony) and one of only a handful in that orchestra’s history — I also share that distinction with Charlie. When I came to Denver, he pulled me aside and told me to both ‘represent’ and be a role model — I have tried to make good on those requests over the years.”

Even as he broke down barriers in the classical world, Burrell never turned his back on jazz. He played in Denver’s legendary Five Points neighborhood alongside some of the greatest jazz musicians of the 20th century. In smoky clubs and grand concert halls alike, his bass lines were the steady heartbeat of every ensemble he joined.

During the 1950’s, the jazz scene in Five Points was the only one between St. Louis and the West Coast, so it became one of the most alive in the country, often being referred to as “The Harlem of the West”. He played in the first integrated jazz trio in Colorado, the Al Rose Trio, and rose to be a central player in the Five Points jazz scene by becoming the house bass player at the Rossonian Hotel, considered the “entertainment central” spot in Five Points during that era.

“I’m proud to call Charlie a friend and colleague,” said William Hill, longtime Principal Timpanist for the Colorado Symphony. “When I was first in the symphony, Charlie hired me regularly for jazz gigs. It was always such a joy, we just listened to each other, and it always worked! Charles brought me much personal joy and I know he did the same for so many others. What a wonderful life of sharing his love for music and people.”

“I’m proud to call Charlie a friend and colleague.”

William Hill, Principal Timpani (retired)

Burrell’s musical gifts were matched only by his generosity of spirit. Whether offering guidance to younger musicians, visiting the sick in hospitals, or volunteering his time and energy to community causes, he lived a life of deep service.

“He had the heart of a lion and the endurance of an elephant,” said Purnell Steen, jazz pianist and Burrell’s cousin. “He was the most benevolent man. He was always giving. However, you didn’t want to cross him. He was small but mighty.”

To his family, Burrell was both hero and human being — a man who practiced at dawn, who cooked fish fries, who quietly changed the world without ever asking for applause.

“My uncle was someone who walked in excellence,” said GRAMMY-winning jazz singer and niece Dianne Reeves. “He was about being the best at what he did and I witnessed that. Staying at his house, four in the morning before the birds started chirping, he would be practicing.”

“He could not grasp the magnitude of what he did,” added Steen. “He said, ‘All I want to do is play music.’ He did not get the credibility he should have gotten, he did not get the notoriety. He lived for three quarters of a century in splendid obscurity and we don’t want his footprint to be erased.”

But perhaps Burrell understood better than anyone the true value of a life well-lived. In the prologue to his autobiography, The Life of Charlie Burrell, he wrote:

“I can sum up most of what I was doing in life in a very few words. It was a matter of love for the profession and love for the people. And that’s about how simple it was.”

Burrell leaves behind a legacy that spans generations. He mentored countless musicians, helped shape Denver’s music scene into one of national renown, and proved — again and again — that music can be a powerful agent of change.

To those lucky enough to have heard him play — or to have known him — Charlie Burrell will forever be a towering figure. And while the music he made may now fall silent, the echo of his impact will resound in concert halls, classrooms, and communities for generations to come.

Charlie Burrell didn’t just play music. He changed it. And through it, he changed us.