On any given evening with the Colorado Symphony, you could find yourself in the midst of a master work by Beethoven, Mozart, Mahler, or similarly immersed in the contemporary music of Prince, The Flaming Lips, Jim James, or Aretha Franklin. In an effort to guide concertgoers, orchestras across the country classify their events into categories that briefly encapsulate a theme or genre; even though all of it is spectacular symphonic music. The distinctions — namely pops and classical — help guide patrons, but they also illuminate a barrier that exists between these two distinct musical worlds.

Enter Steve Hackman, a composer, conductor, producer, and a leading voice among a new generation of classical musicians intent on redefining the ‘classical’ genre by creating imaginative hybrid compositions that blur the lines between high and pop art. This style applies modern musical techniques to the classical repertoire and vice versa. The result is evocative works, commonly known as mashups, that are both derivative yet wholly original.

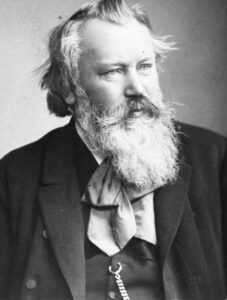

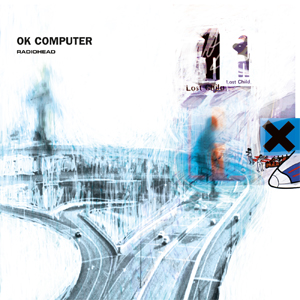

On June 1, 2019, Hackman conducts the Colorado Symphony premiere of Brahms V. Radiohead — his melding of Johannes Brahms’ iconic First Symphony (1876) with Radiohead’s seminal electro-rock album, OK Computer (1997).

Using a process of de- and re-construction, analysis, and re-creation, the program utilizes a full 70-piece orchestra and three vocal soloists as Hackman intertwines all four movements of the First Symphony with eight songs from OK Computer. The result is a collaboration over a century in the making as Hackman pushes the musical envelope, superimposing Radiohead songs above Brahms’ music, altering Radiohead’s melodies to coexist with Brahms’ harmonies, and interjecting the philosophies of one into the other, creating a compelling and captivating new world that captures the essence of both works.

“The piece stays in the romantic sound world of Brahms, using only the instruments he would have used to debut his Symphony, but woven in, superimposed, and inserted are the melodies and music of Radiohead,” writes Hackman on his website. “At times we hear the melodies and words of Radiohead suspended over Brahms’ original music; at times we hear the orchestra playing the music of Radiohead but with the dense counterpoint Brahms. Every combination is explored, and we constantly move from one to the other, but the piece is seamless and many times the audience is left wondering which is which, and how the combination was even possible.”

The two works do share similar defining characteristics. Most significantly, there is a pervasive mood of anxiety and unease that permeates each.

Brahms was famously plagued by the omnipresent shadow of his idol, Ludwig van Beethoven, needing more than two decades to finish his First Symphony as the pressure of being heralded as his successor mounted. “You have no idea what it’s like to hear the footsteps of a giant like that behind you,” said Brahms. In the end, he was able to conquer his symphonic demons by embracing the past in a composition that both echoes the work of Beethoven and simultaneously stands alone as a monumental symphonic work.

For Radiohead, the dread was existential as themes of social alienation, consumerism, emotional isolation, and political turmoil were channeled through each anxiously electric note and lyric of OK Computer. The footsteps they heard were a warning of humanity’s impending overreliance on technology, and this album foretold a societal monotony resulting from the need to capture memories rather than living them — Radiohead saw social media coming before it happened. To convey this unease, Radiohead, unlike Brahms, turned away from their past, discarding the Britt Pop and Rock sound from their first two albums — Pablo Honey and The Bends — instead creating a unique blend of guitar rock and electronica that would become a defining sound of the New Millennium.

Brahms vs. Radiohead and Hackman’s other symphonic mashups are not without their critics. Some consider the deconstruction of such beloved works to be akin to sacrilege. Others contend that classical and contemporary music belong in their own separate categories and shouldn’t be changed or altered in any way.

“A lot of people would say that music like this doesn’t belong together, possibly, and they would say there are barriers between these musics, and they’re categorized into sort of artificial different camps,” said Hackman to Grammy.com. “In my mind, and I think in the mind of many of the musicians on this stage, those barriers are artificial, and they’re in our minds, and if you can’t see them, are they really there?”

In a post on his website in May 2018, Hackman further addressed these criticisms: “Some may purport that these two pieces are separated by more than just time. They may seek to label and categorize them, and perhaps judge their respective and comparative values accordingly. I believe that the more we truly understand the creative and technical processes that result in any kind of art — regardless of genre or category — the more similar they will reveal themselves to us.”

Hackman’s creation exemplifies music as a living, breathing organism. Utilizing two of the great musical works of all time, he shows both their similarities and differences in a creative tapestry of sound that is a delight to behold. So, where Radiohead eschews tradition, Brahms maintains it, but both share a kindred spirit: They are visionary, unrivaled and, for one night, co-headliners at Boettcher Concert Hall.

This article first appeared in the 2019 spring edition of Soundings, the Magazine of the Colorado Symphony.